Robert Hamilton

“If you fall off a cliff, you might as well try to fly.”

--As told to Robert Hamilton by a fellow artist

Robert Hamilton, Not Till the Fat Lady Sings, III-5, oil on board, 1997

About a week before the Covid-19 Virus shuttered most businesses and non-profits in Maine, I was asked by the owner of a local gallery to write an essay on an artist, Robert Hamilton (1916 – 2004). He passed more than a decade ago and few beyond family, neighbors, and former students have ever heard of him. When I previewed the works in person at the Dowling Walsh Gallery, Rockland, Maine, the unedited exhibition was propped up against the walls in two spacious, high ceilinged galleries. The sequencing of his work then, and, quite probably whenever the exhibition is eventually installed, does not really matter too much. Juxtapositions invariably blow off sparks whichever works are placed next to each other. That, as much as anything, is what makes this uncontainable, voluble artist noteworthy. He created the kind of work that must be seen in person, not least because reproductions are hopelessly inadequate, even off-putting. Photographs can’t replicate the in-between-ness of flat colors, scratchy, bumpy textures, overpaint and oozing skeins, the raw edges—the artist’s skittery, eliding touch--or the varying scale of these paintings that range from hand-held intimacy to imposing wall-size mural. They embody the very argument for making exhibitions in the first place while sundering all pretense of art speak discourse about “the hang” of an exhibition. Mostly from the last decade of his life, these paintings shout across the room or whisper their secrets sotto voce just when we think we are done looking. The show is now scheduled to open sometime in the fall of this year but as all of us have learned, planning in the era of coronavirus is only a series of contingencies that follow dictates outside human agency and comprehension.

Although, you would never know it by looking at his work, the artist spent most of his non-teaching career painting on the coast of Maine in a studio overlooking the picturesque harbor of Port Clyde and Teel’s Island, subjects of N.C. Wyeth’s iconic 1935 painting, Island Funeral, among thousands of paintings by artists waiting to board the boat for Monhegan Island and its longstanding artist colony. The fetch, as local fishermen might say, is Portugal. His small but appreciative audience was mostly fellow artists, many of them his former students. In the last decades of Hamilton’s life his closest friend and neighbor, surprising to most, was Andrew Wyeth who genuinely liked his work. To most observers, the left-over-house-paint palette, off-hand roughness and non-sequitur imagery resist easy looking. He rarely spoke about what inspired individual images that always appear loosely moored to a fabulist’s narrative. Like spindrift blowing across an ocean ledge in Muscongus Bay, his was a world of shifting, floating recollection, never to be fixed or finished, warning of unfathomed depths and pulling, cross-tidal currents. The work of Robert Hamilton has rightly been called “the best kept secret in Maine.”

Each summer his neighbors and a few former students would make their way down a dead-end road in Port Clyde where Hamilton would install an exhibition in his own hand-made “museum, in actuality, a rough-hewn high-ceilinged octagonal shed ringed by clerestory windows providing the only illumination. Not only was his work a secret to most collectors, students, and curators with an interest in contemporary art, Hamilton was indifferent to his place in an art world he more or less abandoned when he moved to Maine in 1981 after teaching at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) for 34 years. His idiosyncratic paintings are variously inhabited by anonymous figures including tennis players, masked bandits, nudes, and bellhops who double as train conductors, museum guards, circus performers, military heroes, fellow artists, fighter pilots, opera singers and a menagerie of lions, tigers, and ‘Oh, my!’ characters snatched from dreams and his free-floating, unbounded imagination.

Robert Hamilton, Billiards Player, oil on board, 1999

Within his dimly lit “museum,” Hamilton conjured visions of what piqued his wandering sense of wonder, mystery, meshes in the afternoon imagination. He was a true shaman of those magic places of visual dissonance and stumbled upon surprise that often slip past each other--like strangers on a train, albeit one of his trains as abutting panels traversed the octagonal layout of restless, mysterious travel and travail.

Hamilton grew up in Seneca Falls, New York, birthplace of the women’s suffrage movement and where the artist seems to have absorbed deeply held values that un-conventional, anti-authoritarian, and passionate individuality are what truly matter. Nurtured by brief, glistening, lakeside summers and long isolating winters of the Finger Lakes region, he was a child of the interwar years. Hamilton was born in 1916, the same year as the bloodiest battles of the Great War—Verdun and the first battle of the Somme with over a million casualties. It was the year Norman Rockwell published his first cover for The Saturday Evening Post, an artist Hamilton aspired to become but came to doubt as he experienced rural America during the depths of the Great Depression. Bemused curiosity tinged with regret and darker realities emerged from other places, other ways of seeing, too.

During World War II Hamilton flew over 100 combat missions in a P 47 fighter-bomber and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, an honor he shared with Charles Lindbergh, Amelia Earhart, and George H. W. Bush, among a small, select group of heroic aviators. The Distinguished Flying Cross medal is second only to the Medal of Honor, awarded for valor and extraordinary heroism. Not surprisingly, he was fearless as an artist, and much of Hamilton’s best work relates to arrivals and departures—on bicycles, planes, trains, automobiles and boats. In these and other paintings, we have the sensation of having just walked into the middle Federico Fellini film as re-cut by the Coen brothers. While his muted, some would say wintry, New England humor does not accommodate the Coen brothers’ murder of an armless, legless actor for a more reliably profitable chicken, Hamilton’s vignettes similarly recount fate’s macabre, thin smile: images of fat, clunky P-47 fighters scudding across cloudless skies, as he twice flew his plane into the ground during the War (didn’t trust the parachutes he packed himself). Improbably, he managed to walk away both times unharmed. Indeed, the planes in his paintings more closely resemble Hamilton’s ubiquitous cigar than anything that could possibly fly, much less menace his stylized, commedia dell’arte companions. Those side-long glances aren’t there for nothing.

Hamilton, Sitting Ducks, oil on board, undated

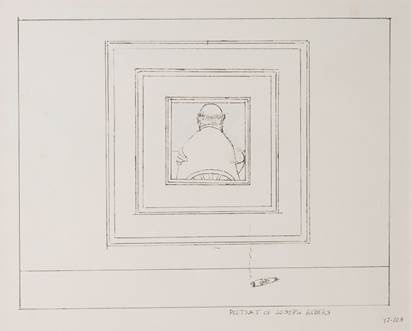

Robert Hamilton, Portrait of Josef Albers, 1997

Hamilton paid homage to a small number of artists he greatly admired: Thomas Eakins, the rule and convention breaking artist-teacher of the 19th century who got himself fired from the Pennsylvania Academy of Design for his radical ideas and teaching methods, was surely a hero; Max Beckmann, a German expatriate and also an artist-teacher, whose mysterious imagery, airless rooms, and stylistic independence anticipated Hamilton’s own; and especially Philip Guston, whom he knew personally and whose hooded terrorists are undone and revealed by cartoon banality and Guernica-like naked light bulbs.

Hamilton’s affectionate though pointed drawing of Josef Albers, who taught just down the road from RISD at Yale, shows the master of color interaction and “Homages to the Square” inside black and white concentric squares. We see Albers from behind, seeming to hug or pat himself on the back. The Windsor chair rhyming with his bald head and slouching shoulders, Hamilton’s winking jape at squares and right angles, perhaps. Hamilton always believed theory hindered experimentation and the imagination. Most of all, Hamilton painted like the improvisational jazz-man he was. He reveled in the glittering solo runs by Louis Armstrong, Bix Beiderbecke, Colman “the Hawk” Hawkins, and especially his own son, the world-renowned jazz, tenor saxophone musician and composer, Scott Hamilton. Jazz is visual in Hamilton’s work—chromatic keys changes, riffs and “sampling” from favorite subjects and artists that resolve into echoing rhythms, call and response chords, a virtuoso “touch” that looked but was far from accidental. The process of “performance” and play was the source of his and all of the art and artists that mattered most to him.

As those who knew him might have expected, he wrote his own obituary where Hamilton tells us matter-of-factly what and why he painted: “I knew my paintings had to be improvised, spontaneous, made up out of whole cloth, one thing leading to another, accidental, a series of metamorphoses, surprised arrivals.” It is worth noting that often these “surprised arrivals” not only surprised the artist but speak to a new generation of figurative painters like Peter Doig, Katherine Bradford, Inka Essenhigh, and many rising stars on the contemporary art scene. For much of his career, Hamilton’s emotion-mapping meditations are assembled from the bits and pieces of his own life’s abundant bricolage. Like so many celebrated masters throughout history, Hamilton’s genius may yet teach current and future generations, even if they don’t know it yet.

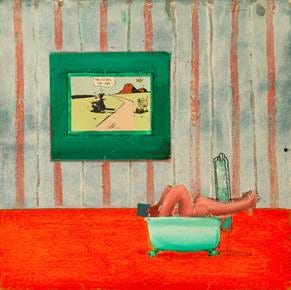

Hamilton, Come Back Sweet Mama (Boy in Museum), oil on canvas, undated

An avid recreational tennis player, Hamilton transcribed a 1920’s newspaper photo of French Wimbledon champion Suzanne Lenglen (1899 – 1938), forever suspended in mid-stretch for a low volley. The match is here “refereed” by a masked museum guard, theater usher, train conductor, or bank robber who is, of course, Robert Hamilton. Lenglen died young and very suddenly in 1938, the year before Hamilton graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design, and the year the world shifted on its axis—Germany’s unopposed, blitzkrieg invasion of Czechoslovakia that would change Hamilton’s life irrevocably. Lenglen’s passing may be seen as signifying the last moment when the world’s and Hamilton’s own innocence was permissible, could be celebrated, was even conceivable. The hushed, gallery-like setting and low light level suggests a fading hope that some museum somewhere (if only his own) might preserve a cropped and fragile memory of their passage--masked museum “guard” notwithstanding. Now rapidly aging and going blind from macular degeneration Hamilton knew this: time is a thief.

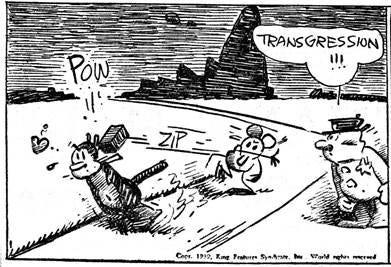

Hamilton kept comic strips of Krazy Kat pinned to walls in his studio (he loved real cats that often padded and purred their way across his drawing table adding paw prints to works in progress). Krazy Kat was created in the first decade of the twentieth century by George Herriman. It was among the earliest recurring comic strips that first appeared in newspapers in 1913 and was nationally syndicated through 1944, neatly bracketing Hamilton’s own childhood and art education. Herriman’s strip was modestly popular during the nineteen-twenties, thirties and into the War years—e e cummings was a fan--but has since become a touchstone for many artists, cartoonists, and graphic novelists.

Hamilton, Untitled, oil on board with collage, undated

In one memorable, maniacal backstory line, Herriman’s Krazy Kat has an ancestor, a cat named Marc Antony, who falls in love with an Egyptian mouse who returns his love, oddly but affectionately, by throwing bricks at him/her (genders are ambiguous). Like some DNA defective trait passed down through countless generations, Krazy Kat inherits his/her infatuation with a mouse named Ignatz. Thus, Krazy Kat believes the bricks thrown at him by Ignatz are pre-ordained love-taps. Stalked and harassed by the cat, Ignatz feeds Krazy’s ancestral fantasies by continuing to toss bricks in a never-ending and endlessly repeated cycle of emotional mayhem. Hamilton was a life-long fan of the strip who introduced it to his former student, Richard Merkin, the renowned New Yorker illustrator and cartoonist.

George Herriman, “Krazy Kat” cartoon panel, 1939

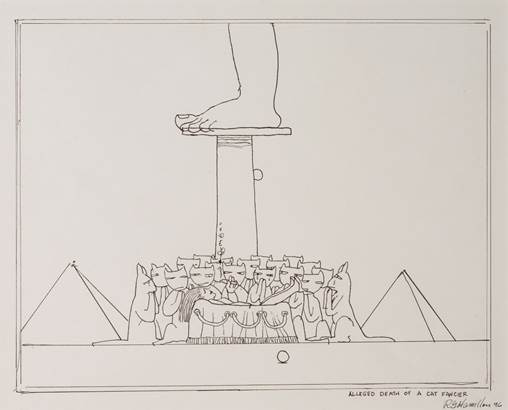

Hamilton’s Egyptian references undoubtedly spring from multiple sources. Art school basics--pyramids, cones, cubes and cylinders needed somewhere to go. Why not Egypt? Egypt and its building blocks are the very origins of Western art history when Hamilton was a student at RISD and later teaching there. But, sphinxes, deserts, and Horus-faced crews, sculling (pace, Tom Eakins) madly, eternally along the Nile toward nowhere and nothingness, appear also to recall Hamilton’s boyhood infatuation with a comic strip that could only make sense to childhood fantasy. In the remarkably long life of the strip we know that Krazy Kat’s love is never returned by Ignatz.

Hamilton, Counter Intelligence, oil on board, 1999

Within Hamilton’s universe of misfits and affable strangers, Krazy is feline kin to his series of “Fat Lady” paintings--she, who never quite gets to sing. There, the cavorting nudes perpetually balance upon, chase, caress, poke, dodge, and look at beach balls—colorful spheres that occasionally moonlight as hot air balloons (or cupcakes, targets, billiard balls, and breasts)--floating in and out of airless, evenly lit stage sets.

They and Krazy and all of the other oddly costumed and pre-occupied actors appear as silent witnesses to and reminders of a brick-bouncing-off-his-head ever-present truth—at least for an artist who needed to paint every day of his long, prolific career. Hamilton was never dissuaded by brickbats of a fraught, cruel century. For Hamilton what mattered beyond reason was a never-ending, unrequited love affair with those “surprised arrivals.”

Bob once told me that as a fighter pilot in WW II, he had been ordered to strafe cows and other farm animals on his return from bombing missions over Germany to his home base. He refused to murder animals (and their owners) so he would empty his machine guns into uninhabited forests and fields. Among a handful of wartime pilots who flew and survived over 100 missions, I think Bob likely believed that every day he lived after his wartime experiences was a gift, especially if he could make artworks that in dream-like imagery and processes--literally clawing back light from blackness--that also became thankyou notes to the universe--Paper Moons he saw on many return flights--for saving his life, allowing him to process what he had endured. Crazy like a very cool cat he taught himself to fly in realms of the spirit and imagination.

Robert Hamilton, Alleged Death of a Cat Fancier, 1996