Neil Welliver

Landscape painting in Maine

Neil Welliver (1929 – 2005)

Marsh Shadow, 1984, oil on canvas, 96 x 96 inches

O, summer in Maine! Nearly every art museum and commercial art galleries across the State are showing Maine landscapes by an eclectic mix of regionally prominent and nationally respected living artists. Even abroad, Maine artists painting Maine are being featured: Lois Dodd at the Kunstmuseum den Haag in the Netherlands; Nicole Wittenberg at the Fondation le Corbusier in Paris. Paintings of wetlands, songbirds, moons and wildflowers and some that verge on total abstraction owe much to precursors like Rockell Kent, John Marin, Marsden Hartley, Fairfield Porter and, of course, three generations of the Wyeth family.

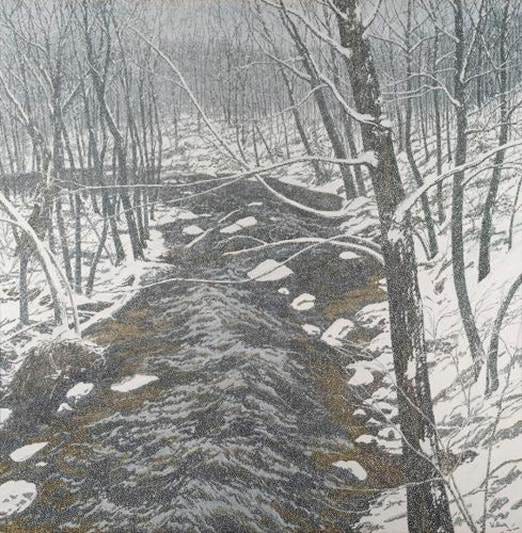

But it was Neil Welliver, whose magisterial, peripheral-vision enveloping views of Maine’s untamed, uncontrollable, semi-abstract, natural beauty that opened the door for what has become “the new landscape” painting of recent years. It is worth noting that Welliver, alone among his contemporary peers, painted interior Maine in all seasons. Summers were not so much celebrated as endured with black flies and bloodthirsty mosquitoes attacking Welliver mercilessly on his several trips along the Allagash River in northern Maine. Winter and mud-seasons presented their own special challenges to a process whereby keeping brushes, paper, and canvas dry while maintaining the viscosity of oil paint in near zero temperatures became critical issues. It is, then, overdue in Maine and a welcome opportunity that a substantial group of Welliver’s signature paintings of Maine’s unsettled back country meadows, buried valleys, steep hillsides, and remote streams are being shown this summer [dates] in nearby Rockport (at the former CMCA gallery, now privately owned), courtesy of the Alexandre Gallery, New York, which represents part of Welliver’s estate.

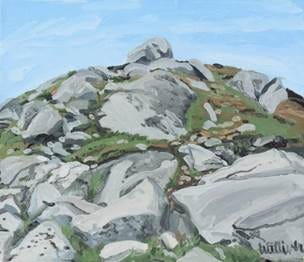

Welliver routinely traversed inland thickets of tangled brush or ice-encrusted river and stream shorelines. Their imposing physicality is a reflection of Welliver’s process, achieved through immense physical effort and a unique studio practice including his strictly limited palette (eight colors plus black and white) with adjacent colors optically mixing to create subtle, flickering tonal gradations (a trick he undoubtedly learned at Yale from his mentor Josef Albers). The artist’s paintings are tough, raw, unromantic, remote. They pull the eye across and into the dabbed painterly surfaces where texture and image converge. The eminent critic, Robert Hughes, in his encyclopedic survey of American art, American Visions, describes one of Welliver’s paintings: “The hill behind you becomes a presence: a sign of what the Middle Ages called natura naturans—nature going silently about its business of being.” Streams cease gurgling, birch tree leaves do not rattle in the wind because our awareness of the primacy of paint muffles reality.

Welliver’s Winter scenes are bone-cold, icy with a sense of greyed, atmospheric wetness infusing the stillness and every streamside broken branch. His scrims of lightly falling snow, composed of countless dabs of white paint pulling the eye to the foreground from within the depths of a receding landscapes, are among the most arresting winterscapes in the history of art. In all of his paintings, he reclaims a painterly abstraction and surface flatness while simultaneously acknowledging nature’s infinitude just beyond a hill or glimpsed from high horizons. Driving home their non-photographic origins as artificial hand-worked, independent objects, nearly all of his oil paintings are square—arbitrary height equals arbitrary width—a modernist convention from the late 19th century. The largest, most densely and freely brushed paintings marry Jackson Pollock to Andrew Wyeth.

Snow on Alden Brook, 1983, oil on canvas, (collection of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art)

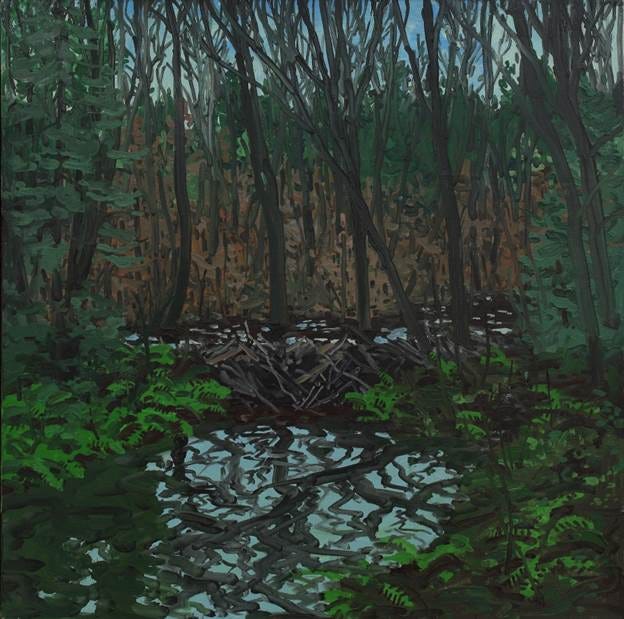

Beaver Dam, n.d., oil on canvas, 24 x 24 inches

The large, wall-size paintings always begin with on-location drawings and oil studies. While some of the small oils and drawings are scaled up in the studio to become monumental landscapes (fully eight by eight feet or larger in some cases), the studies stand as fully finished and spontaneous reactions to a particular place and moment in time having caught the artist’s eye, often for a seemingly non-descriptive abstracted-ness. Curiously, although his best-known Maine paintings were all completed at his Lincolnville, Maine studio, and he lived only a short distance from picturesque Penobscot Bay, he never painted seascapes. Most often, he was drawn to small streams and the steep foothills, reminiscent of his youth growing up in rural Millville, PA, That, and he had a contrarian streak, compelling him to look for non-descript, “ordinary” places others would find too hard to get to, too tangled with undergrowth, too boring, or just too damned ordinary. Welliver was congenitally predisposed to making “difficult” art; that is to say, he liked the physical challenge of obstacles, especially those served up by nature. Finding places that only locals or beavers or osprey had ever seen before suited his own prickly nature, personal sense of discovery, and need for private, isolated experience.

Big Flowage, 1979, oil on canvas, 96 x 96 inches

Welliver’s woodcut prints, composed by the artist in collaboration with a traditionally trained Japanese master of the woodblock printing technique are indebted to 17th and 18th century Japanese Ukiyo-e prints. In addition to citing the very origins of modernism in the hands of the 19th century French avant-garde—shadowless figures, unmodulated color, ambiguous spatial relationships--the prints, perhaps most of all, address Welliver’s personal “floating world” of shimmering brook trout and gracefully-necked and richly colored water-fowl, beaver ponds, tree stumps and osprey, the sole inhabitants of Welliver’s own floating, hidden worlds.

Ukiyo translates from Buddhist expression as “between grief and sadness,” not coincidentally haunting the loss of Welliver’s life’s work in a 1975 fire, followed by the deaths of an infant daughter and his wife within the same year, and, several later, the loss of a son to disease, and the murder of another of his sons who was traveling in southeast Asia. While continuing to teach after the fire in 1975, his own painting became more narrowly focused on nature alone, as he gradually eliminated the human figure from the landscapes. It is tempting to imagine grief subsumed in the birch trees, rock-strewn streams, and flickering glimpses of bright blue skies. But there are no hints of sorrow, save caressing brushwork and crystalline still air. And, Welliver never revealed, except in his art, what thoughts followed him on those solitary long hikes with a 70-pound backpack he took into the dark recesses of the deepest Maine woods.

Barren, 1981, oil on canvas, 12 x 14 inches

In 2018 a former student accused Welliver of sexual harassment in 1971 during his teaching career at the University of Pennsylvania. We know that trauma sometimes takes years or even decades to reveal itself. However, nearly half-a-century on and with no subsequent corroboration or additional allegations, it must be acknowledged, too, that Welliver is unable to defend himself from the grave. Welliver’ life--with its heart-ripping tragedies and what poet and friend Mark Strand called, “that wildness…” which gives his work such power and resonance--was complicated. There is no defense for the indefensible nor can we know the unknowable. Welliver would surely want those who love his work to look for him in his silent homages to an obdurate nature--cleansing, redemptive, true.

Flotsam, Allagash, 1988, oil on canvas, 48 x 48 inches

Christopher Crosman

Thomaston, Maine, June 2025