Bo Bartlett

Works on Paper

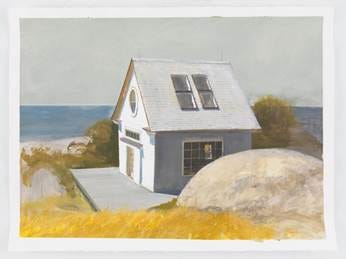

Betsy’s Studio on a Gray Day

On this island there were no human ghosts, no ghosts of any ancient race. The sea, and the spume and the wind and the weather, had washed them all out, washed them out, so there was only the sound of the sea itself, its own ghost, myriad-voiced, communing and plotting and shouting all winter long. And only the smell of the sea, with a few bristly bushes of gorse and coarse tufts of heather, among the grey, pellucid rocks, in the grey, more pellucid air. The coldness, the greyness, even the soft, creeping fog of the sea! And the islet of rock humped up in it all, like the last point in space.

D, H, Lawrence, “The Man Who Loved Islands,” 1928

Of course, Lawrence’s protagonist, Cathcart, was only trying to find escape from the horrors men do to other men and to themselves in the aftermath of muddy trenches, blood-soaked river valleys, and desolate fields that was the first “Great War’s” legacy. Nothing could be further from Bartlett’s own enterprise—except, perhaps, those great mysteries of nature that islands seem to hold more closely, even jealously against a too busy, too loud, too unfocused world. That said, there is, too, in Lawrence’s island soliloquy and in several of these fresh-air infused paintings a quality of solace and renewal. Bo Bartlett’s relatively small gouache paintings, produced during summers in Maine between 2016 and 2017 come as something of a respite from the larger, dramatic and metaphor-infused, more intellectually and psychologically charged, and seemingly more ambitious paintings for which he is best known. Seemingly, because the smaller works have their different levels of complexity, metaphor and magic. The gouaches are the embodiment of those recurring, peaceful interludes of island life between loving and working and a kind of symbiotic coalescence of the two that, for artists, island living gently enforces for lack of alternatives or modern distractions. And while their purpose may be, as Bartlett himself notes, warm-ups for the large oils, they are quintessentially evocative of those things the artist most treasures at the level of why he paints—how a brush and pencil can carve structure, shoreline, ledge and human presence—from light and air. Gouache, although water-based, is an opaque medium that allows revision and has greater texture than watercolor. It also rewards a certain lightness of touch as luminosity is enhanced by light hitting its multi-faceted, chalk-like molecular structure. It is a medium that in skilled hands is conducive to evanescent effects like fog, twilight, blanching sunlight or the littoral revelations of shorelines between the rise and fall of tides, where the medium elides into what is represented—Lawrence’s pellucid rocks and air. If these are mere “warm-ups” for the artist, they are also the most direct and accessible way into work that begins and mostly ends with nature’s—including human nature’s-- eternal rhythms and fluid meanings as colored and washed by memory and personal experience.

Bo Bartlett and his wife, painter and musician Betsy Eby, spend summers on Wheaton Island in mid-coastal Maine where they designed their similar, though separate, studios variously depicted from different angles and viewpoints as seen in many of the painting in the current exhibition. The studios, their renovated 1905 fisherman’s cottage, and outbuildings nudge up against the land and rocks like the local Puffin nests located on remote Matinicus Rock, a protected wildlife sanctuary housing these small, endangered seabirds. Nearby Matinicus Island (not to be confused with the Puffins’ more distant islet home) is about 22 miles out to sea in the Gulf of Maine, farthest from the mainland of any year-round, inhabited island in the Maine archipelago. From the Bartletts’ ocean-facing studios on Wheaton Island at the entrance to Matinicus harbor, the fetch, as the saying goes, is Portugal with nothing but open-ocean between. Looking east across the sea from their small foothold on the island, the view takes on vast connotations that affect their daily lives—transportation, shelter, food, work and rest and how these are affected by large and small shifts in wind direction; neither politics nor even art seem to matter so much. Weather is a life and death topic of conversation here.

They named the house on Wheaton Island “Stillpoint” after a passage in T. S. Eliot’s “Burnt Norton” from his “Four Quartets,” the poet’s celebrated late-in-life meditation on time and its passage, “neither from nor towards.” Eliot, [named for the poet?] Bo’s youngest son passed away several years ago and according to the artist, “we started construction [on the studios] the year after Eliot passed away…in part as a way to survive.” Along with these studios—places of spiritual and physical creativity--there is no more eloquent memorial than Bartlett’s “Blue Skies” series of paintings that invoke a favorite song, “Blue Skies” loved by both father and son and a modest hit by the British indie group, Noah and the Whale. With its message of better, brighter times, the small, monochromatic paintings are the product of countless hours spent focusing on singular, cloudless patches of clear, blue sky at different times of day and from different angles. Among other challenges was the lack of any focal point and the artist’s fierce need to record “real” sky in real time—rendering nothingness real. The excruciating process lends these obsessive paintings their poignancy, testament, no doubt, to the pain of being in such a moment. Several of the gouaches in this exhibition rehearse a crystalline, uninflected Maine sky: Binaries, with its azure, cloudless horizon above the poignantly empty white Adirondack chairs and nearby studio; and in High Tide, among the most ravishing paintings of the entire series, the blinding interior view through open French doors and transom light, perfectly framing different segments of intense, colored light that seems to have been inhaled by the room itself. For Bartlett, “painting is a living thing.”

High Tide Binaries

Paintings like those and many others included in the present exhibition recall several of the artist’s heroes from Eakins to Homer, from Hopper to Andrew Wyeth, all of whom Bartlett acknowledges and occasionally quotes or indirectly paraphrases in his own paintings. But it may have been Andrew’s wife, Betsy, who affected him most deeply, especially in the context of Bartlett’s cinematic sensibility and, also, in the spare precision and “camera eye” cropping of these quintessentially coastal Maine gouaches. Over the course of four years, in the early 1990s, Betsy and Bo worked closely together on a retrospective documentary film of Andrew’s life and work entitled, Snow Hill. The entire structure of Snow Hill, its rhythms, measured pacing and sharply clipped cadences, dissolving montages, as well as the use of stillness, minimal, terse narration, doorway- and window-framed shots, and even the Edenic ardor of the Shaker hymn-laced soundtrack, belong to an aesthetic sensibility, shared with, Bo, but honed by Mrs. Wyeth over fifty plus years of looking at, gently influencing and confirming her husband’s enigmatic work. Bartlett directed the film and his own well-developed cinematic sensibility coincided with Betsy’s minimalist point of view in Snow Hill. It’s within reason to suggest that Bartlett’s sense of movement and sequence in these gouaches can be viewed, however indirectly, as homages to Betsy Wyeth, an often overlooked mentor and creative catalyst in her own right whose buildings on Benner and Allen Islands became settings for her husband’s late paintings. Unquestionably, she would respond to the quietude found in these gouaches.

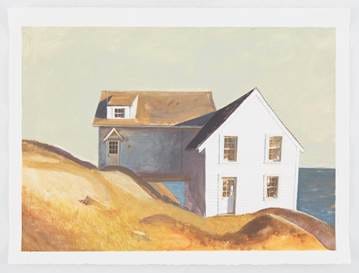

Island Studio

Island Studio is a case in point. Betsy Eby’s clapboard studio structure rises, sentinel-like, resolutely crowning the yellow curve of a grassy knoll. Fluttering blue pennants of oceanic welcome embrace the studio from the left and right horizon lines, accounting for the reflected blues and turquoise colors scuffing the pristine, white clapboard siding, eaves and gable returns. An echoing gabled roof extension is centered discretely on the building’s back wall. Evoking 19th century fishermen’s cottages and outbuildings, the structure discretely suggests its 21st century function with ample, skylights. No other marks interrupt the white, hazy summer sky that is, in fact, the untouched Arches watercolor paper.

Outpost

Betsy’s Studio, Island Studio and Outpost show the same architectural form from several points of view and at different times of day. As with every gouache in this group, qualities of summer light are the center of attention, supported by perfectly tuned, call and response discourse between organic and geometric forms, freedom and control, movement and stasis, representation and abstraction.

Ledge House

Where Island Studio seems strongly anchored to its site and well back from threatening seas, Ledge House, is akin to the aforementioned Puffin’s nests, barely clinging to its granite ledge outcropping over which the artists’ home is partially cantilevered (it is unclear whether the right side is even on land). An attached “el” reaches for its own footing bridging the space between ledges, figuratively grasping for whatever might be the builders’ equivalent of a lifeguard’s buoy as it abandons ship. The simple New England structure with an array of clean, carefully balanced six over six windows and chaste horizontal and vertical lines counter the visual instability of the landscape. There is a stripped down narrative implied: only an artist whose life depends on proximity to natural grandeur and to what can only be described as uncontrollable beauty would even consider living here. Anyway, what the locals know about North Atlantic gales is no deterrent to a certain willful madness. Bartlett, after all, paints immense sharks, gutted by a “Virginia Cavalier,” t-shirt-clad youth revealing the shrouded body of another youth in the animal's belly. Part Moby Dick, part Biblical Jonah or Christian Resurrection, and part hallucinatory, campus football weekend bonfire, the painting confirms what native Matinicus Islanders suspected all along. Like Annie Proulx’s Shipping News pirates they’ll salvage the house when it’s swept away and sell the remains to the next crazy artist from Georgia. It’s all part of why Bartlett loves Maine and how he thinks about it sometimes.

That and the moist salt air driven ashore by passing storms like Hermine, a hurricane that brushed Georgia before dissipating in the Gulf of Maine. In Passing Hermine, a tiny white Adirondack chair sits at the composition’s centered vanishing point, just visible in the distance near the crashing surf. The chair pulls the eye into pictorial space and holds you there, suspended between land and sea. It appears to be a blustery, late summer day, still warm enough to sit or paint on Betsy’s studio’s broad deck but blowing enough to think twice about rowing to Matinicus. This and other paintings contain underlying pencil or ink drawing and the thinly applied paint allows the drawing to show though. It’s a technique that Bartlett learned directly from Andrew Wyeth (who learned it by looking at watercolors by Winslow Homer and Edward Hopper). Tension between the rough terrain and churning ocean is played against the planar calm of the flat deck and the oblique, wind-sheltering exterior studio wall. The collision of nature and culture is literally true sometimes.

Boat House

The loose, sketch-like Boat House leaves us to ponder where the boat might have gone, absent its oars leaning against the corner walls. The painting appears unfinished at first glance; it is, however, more a matter of stopping when any painting says all it needs to. Dripping gray fingers of paint point toward the bottom edge as gravity operates in concert with the painter’s decisive stroke, a silent celebration of intentionality, allowing accidents that all artists accept and utilize. Elsewhere, a wall dissolves in layered, swooping washes where yellow-gray and gray-yellow summarize a quality of un-fixed-ness that the tilting ocean glimpsed through the window seems to reinforce. Painting about painting is not exactly new but painting that pictures its own messy, chaotic genesis is how artists reinvent themselves and their work. Warm-up or not, it’s thrilling to witness an artist working his medium, fearless and confident, conscious of and alive to change.

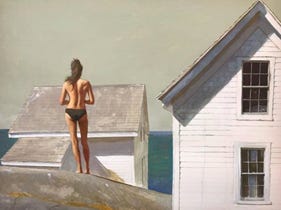

Outer Shoals The Day You Came to Pose

Within the present group of gouaches the only overtly human intrusions are a semi-nude figure in Outer Shoals, who somehow seems overdressed between the expanse of plain white clapboard structures and the unlimited, emptiness of ocean and sky above. In another painting, The Day You Came to Pose, human absence is highlighted by Betsy’s bicycle, an unadorned “cruiser” style bike better suited to the flats of tidewater Georgia than Wheaton’s ice-age terrain of erratic-formed granite outcroppings and hardy, nettle-like vegetation clawing island and islander alike on their barely 20 acre island (at high tide). It is also doubtful his model arrived on the bike (unless it was his wife) but the suggestion of transport and movement is reified by the bike’s shadow on the studio wall—Peter Pan shadow-magic seems an ever-present, albeit elusive companion on their island, well-suited to quick sketches before light dances behind scudding, fair-weather clouds. Bo also keeps a bike there and he and Betsy occasionally ride together or separately exploring their small, wild rock pile nestled on the edge of endlessness. Bicycles are featured prominently in Noah and the Whale’s music video of “Blue Skies.” Bo and Betsy riding or walking the shoreline of their island, their own “last point in space,” in the vastness of the North Atlantic would know that walking an island is to understand endings are also beginnings.

Bartlett loves high art and literature but also pop culture, and his paintings often incorporate multiple references simultaneously--from the Bible to Yeats to Harper Lee to indie rock. Another southern story teller with New England ties, James Taylor, wrote his classic lullaby, Sweet Baby James, for his brother’s newborn son—“he sings out a song which is soft but it's clear--as if maybe someone could hear.” Just so, with his fog shrouded Silent Seas and its sunburnt companion, Station. In some sense all of Bartlett’s gouaches are short, sweet songs sung to himself, softly and clearly, as if others—his Georgia family, the Matinicus fishermen, his wife, his children--are yet close enough to hear. Softly, clearly that is who the paintings are for and what they are about. Warm-ups for the soul.

Aurora Borealis

Warm ups for the soul!!