Anne Neeley

Anne Neely: Looking Now

“A picture lives by companionship… It’s a risky act to send it out into the world.”

Mark Rothko in RED by John Logan

Not since Frederic Churches’ Twilight in the Wilderness, (1860) or Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) has the color red in a painting seemed so portentous, prescient. Churches’ mid-19th century masterpiece, based on an earlier trip to Maine, has been seen by historians as harbinger of catastrophic conflagration on the eve of Civil War, but also as elegy to the loss of American “wildness,” even then threatened by industrial development. And Munch’s intensely saturated red sky suggested to later scientists that his painting is an accurate portrayal of Scandinavian atmospheric effects after the 1883 explosion of the Krakatoa Volcano in the South Pacific that tinted skies a deep red for at least a decade afterwards.

For Neely, her orange-red upward release and seething surface in Evening View is both metaphorical and factual. It can be about the way paint looks and feels at a time when the act of painting cannot escape a damaged world under existential threat from climate change. Paintings that suggest firestorms and sun flares are only the outward associations we, the viewers, might bring to color and touch that, absent associations and current context, are beautifully rendered, dance-like in its rhythms and whipping energy. Neely and her unique painterly processes rehearse nature’s own: release and renewal; mother and destroyer of worlds. This is to say her personal, private points of view are manifested in a practice of pouring, splattering, pushing and pulling paint across flat surfaces until it says something to her. And then, doing it again, and yet again, to let layers of color seep into and under each other and to allow forms to build upon one another, organically, naturally. Dense and controlled, her paintings are tough, hard-won, difficult to fully apprehend. They are personal and local, but not private.

Neely is among those artists born during the middle decades of the 20th century, often derided and dismissed as “Boomers.” But, Neely is also among that generation of artists who emerged at the height of the Vietnam and Civil Rights eras amidst the rise of protest around women’s rights, and whose work often navigated between personal experience and collective, media-saturated memory. They include such different and differently focused and inspired artists as Elizabeth Murray, Ree Morton, Susan Rothenberg, Lynda Benglis, Celeste Roberge, Dozier Bell and Katherine Bradford, among others. Indeed, it is the women of this generation (many with Maine ties) whose work has become, well, generative for a whole new generation of artists working at the frayed edges of contemporary figuration and abstraction and whose work often references personal relationships to materials, media, the natural world, and domestic life. In the teeth of male dominated 1970s and 80s Minimalism and Pop, women artists, like Neely, looked to organic abstraction to describe and comment on issues from climate change to reproductive rights to feminist and racial diversity and equality. Most, like Neely and several of her own students (including Sarah Sze) and associates from Massachusetts and Maine continue to make art as if lives depend on it. For Neely, and those who care to look now and to think deeply, they do.

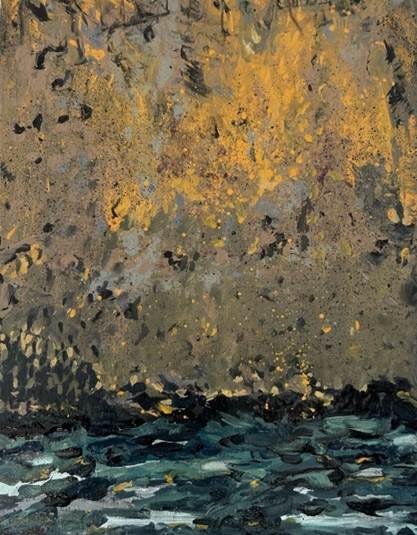

Neely recently observed, “I find purpose in the conversation I have with paint, and I try to find a balance between beauty and foreboding in my work.” Unless we look closely at this small painting where agitated brushstrokes and angry reds and oranges collide, we might not notice the thin, bottom edge is a burnt, charred wasteland, a low horizon of blackened, indeterminate remains of “an evening view,” our own twilight in the wilderness. Then, in another small panel, At the Edge, she gives us its watery reciprocal, a rising, roiling sea under a mist-laden, shroud-like and shredded curtain lifting over a distant, uncertain horizon. Unlike poetry or dance or theater, painting can let us see two things at once—at the edge where conversations about foreboding and healing grace can begin.

At The Edge, 2023, 14 x 11inches,